This article was authored by Phil Marshall, and was originally posted on telecomasia.net.

For many years, web content has been transported over the Internet using the Hypertext Transfer Protocol version 1.1 (HTTP/1.1), running on the Transport Control Protocol (TCP). HTTP/1.1 was published by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in 1997 (RFC 2068), was modified in 1999 (RFC 2616) and in 2014 (RFC 7230-7325), and has been the work-horse for the web for many years. It is also a widely used application-layer protocol for fixed and mobile internet services.

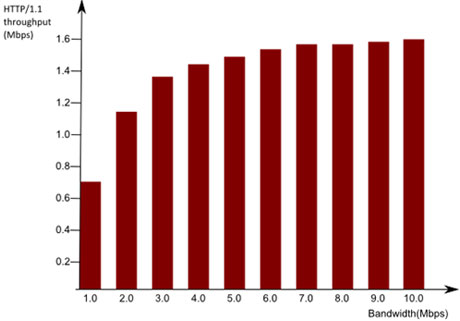

The size and complexity of web sites and internet applications has increased tremendously since 1997 when HTTP/1.1 was first introduced. As a consequence, HTTP/1.1 creates a bottleneck for web performance, as is illustrated in Figure 1. In response, web developers have used a variety of workarounds, such as HTTP pipelining, opening multiple TCP connections to the same host, or in some cases using “website sharding” techniques to distribute web content across multiple servers. While these techniques increase web performance, they create suboptimum queuing conditions for HTTP/1.1, which is essentially a session based protocol. As a consequence, industry players have been debating alternative solutions to upgrade HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/2. Late in 2013 the IETF adopted the SPDY protocol as a baseline for the standardization of HTTP/2. While SPDY offers a variety of enhancements to HTTP, it also has the potential to compromise security, traffic management and policy enforcement regimes in fixed, mobile and enterprise networks.

Figure 1: HTTP/1.1 throttles web performance as bandwidth demands increase

Source: Google 2012

SPDY (which is pronounced ‘speedy’) was originally developed by Mike Belshe and Roberto Peon at Google, with the stated goals of reducing web page load times by 50%, using techniques that minimize deployment complexity, avoid changes to web content and leverage open source developments. To achieve these requirements, SPDY introduced four key capabilities that supersede HTTP/1.1, which include:

- The ability to asynchronously multiplex web resource requests in a single TCP connection and allow for these resources to be prioritized.

- Header compression, and;

- Server push and hint capabilities to improve the web content retrieval process.

SPDY has already been used by several internet heavyweights including Amazon, Google, Facebook and Twitter and technology vendors including Cisco, F5 and Oracle.

As SPDY sees positive market momentum, it has the potential to introduce vulnerabilities in fixed, mobile and enterprise networks. In particular, network appliances are commonly deployed for a variety of network security, traffic management and policy enforcement functions in the path between client devices and web servers. Since these appliances typically expect HTTP/1.1 traffic, they would not ordinarily pass native SPDY traffic. To overcome this challenge, SPDY uses TLS encryption to create tunnels through all the interleaving appliances to the SPDY server to which the client is connected. The network appliances can no longer interrogate HTTP contextual information, such as the Universal Resource Identifiers (URI), and the GET, POST and Connect commands, because they are unable to decrypt the TLS traffic.

Some vendors like Google and Amazon are taking SPDY a step further by implementing SPDY-proxy servers to extend SPDY capabilities from HTTP/1.1 hosts, which are similar to proxy based encrypted tunnelling techniques pioneered by companies like Blackberry and Opera. For example, Google offers an opt-in service for its Chrome browser and Android users to establish SDPY tunnels directly to its SDPY-proxy servers, (known as Chrome Data Compression Proxies). The servers aggregate HTTP connections from the public internet optimize the content and encapsulate and send it to the devices over secure SPDY tunnels. Amazon has a comparable solution with its Silk split browser architecture.

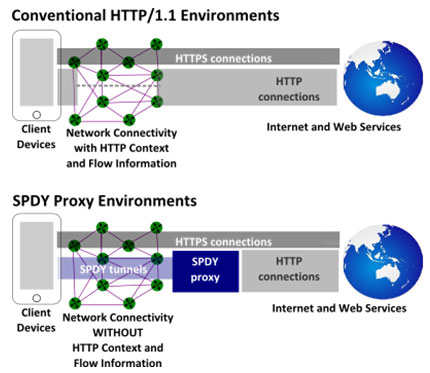

While SPDY-proxies are inevitable as service providers and over-the-top (OTT) players like Google and Amazon look to extend the capabilities of SPDY into legacy environments, the proxies potentially have a tremendous impact on network based security, traffic and policy management regimes. By way of illustration, Figure 2 compares a conventional HTTP/1.1 with the SPDY-proxy architecture that have been implemented by companies like Google and Amazon. In the case of the conventional HTTP/1.1 architecture, HTTP flow information (i.e. source and destination addresses, port numbers and protocols used) can be interrogated by network appliances. However, when a SPDY-proxy is used, the HTTP flow information is lost and therefore there is no means of interrogating the content that is being transported over the network. Carefully crafted solutions are needed to avoid the perils of the “dumb-pipe” networks that the SPDY-proxy architectures create.

Figure 2: SPDY-proxy architectures impact the future capabilities of network appliances

Source: Tolaga Research 2014 and Google

Source: Tolaga Research 2014 and Google

The Open Web Alliance (OWA) has been established by leading service providers and infrastructure vendors to ensure that HTTP/2 implementations preserve the integrity of network based services. We believe that at a minimum the OWA must address the following requirements:

- Security, privacy and parental control

- Traffic management and network load balancing

- Customer experience management

- Regulatory mandates, such as those associated with data management and protection and lawful intercept.

Given the complex network and service environments involved, the industry must focus on common use cases that are likely to be impacted by SPDY and wherever possible, anticipate how these use cases are likely to change as markets continue to mature.

If you haven't already, please take our Reader Survey! Just 3 questions to help us better understand who is reading Telecom Ramblings so we can serve you better!

Categories: Internet Traffic · Other Posts

See mobile alliance tries to hijack users with custom UID in HTTP traffic. This is why they stringly object SDPY protocol which blocks the UID going through an encrypted HTTP traffic.

http://www.propublica.org/article/somebodys-already-using-verizons-id-to-track-users

“the integrity of network based services” = “targeted advertising, censorship, and warrantless surveillance”

Heads up to service providers (who should focus on that rather than extracting rents): we want dumb pipes! If you don’t provide them, at a reasonable provide, we’ll find a provider who will.

“At a reasonable price”, even. 🙂

A fantastic reason to leave the NSP space, thanks!